Essential Insights

- Despite its shortcomings, Lynch’s Dune demonstrates bold visuals and emphasizes the political complexity of the narrative.

- Lynch’s film effectively captured the imperial splendor, presenting an aristocratic feel that is somewhat absent in the latest version.

- This earlier adaptation of Dune contains noteworthy narrative variations and merits a reevaluation for its distinctive style.

When individuals identify as fans of Dune, they typically point to either Frank Herbert’s original literature or Denis Villeneuve’s cinematic rendition. David Lynch’s 1984 adaptation rarely enters these discussions, despite his acclaim for surrealist works. The film was considered too eccentric upon its release. However, retrospective views reveal that Lynch’s attempt succeeded in aspects that his own post-release criticism miss.

Before 1984, attempts to translate Frank Herbert’s epic novels onto the silver screen had proved daunting, with notable directors like Alejandro Jodorowsky and Ridley Scott backing out for various reasons. Lynch was the pioneer in bringing this sci-fi narrative to life, though the outcome was regrettable. The film faced significant backlash and is now often viewed as an example of a failed adaptation, yet it possesses inherent merits that some argue may surpass those found in contemporary portrayals.

Lynch’s Extravagant Vision

Lynch’s version of Dune might not have achieved success during its initial run or even as time went on, especially when compared with the more polished recent adaptations. Nonetheless, its reputation is not as dire as mainstream narratives would have it. Rather, it stands as an ambitious work with commendable elements that deserve recognition.

Visually, the contrasts between Lynch’s and Villeneuve’s adaptations are quite pronounced. Villeneuve’s film presents a sleek and minimal aesthetic similar to his previous project, Blade Runner 2049. In contrast, Lynch boldly employs a more extravagant and unorthodox visual style, enhancing the storytelling experience. While the cinematography in Villeneuve’s Dune is likely to be regarded as timeless, Lynch’s rendition ventures into opulence with its extravagant sets and elaborate costumes, such as the striking Fremen stillsuits, crafting an environment that feels fittingly surreal for the narrative.

Additionally, Villeneuve opts to highlight Paul’s personal story arc, whereas Lynch’s 1984 film delves deeply into the political intricacies of its universe. The portrayal of factions such as the Great Houses, the Spacing Guild, and the Emperor was significantly more pronounced in Lynch’s version, despite this making the narrative feel somewhat fragmented and hurried. However, this intricate lore is pivotal to Herbert’s original vision.

Regal Portrayal in the Original Dune

Lynch’s adaptation excelled in depicting the imperial majesty of the noble houses, particularly highlighting the Corrinos and Atreides. The aristocratic ambiance was authentically rendered, making characters like Princess Irulan exude a sense of royalty. Christopher Walken’s portrayal in Villeneuve’s Dune is notably more reserved, aligning with the film’s tone, while José Ferrer’s portrayal of the Padishah Emperor in Lynch’s version conveys a commanding presence.

Furthermore, Lynch’s representation of Duke Leto and the Atreides family captures a more formal and opulent essence when contrasted with Oscar Isaac’s more understated, “cool-dad”characterization in the newer adaptation. Although Lynch’s film faced criticism for its portrayal of Baron Harkonnen, the villain’s grotesque essence was undeniably potent.

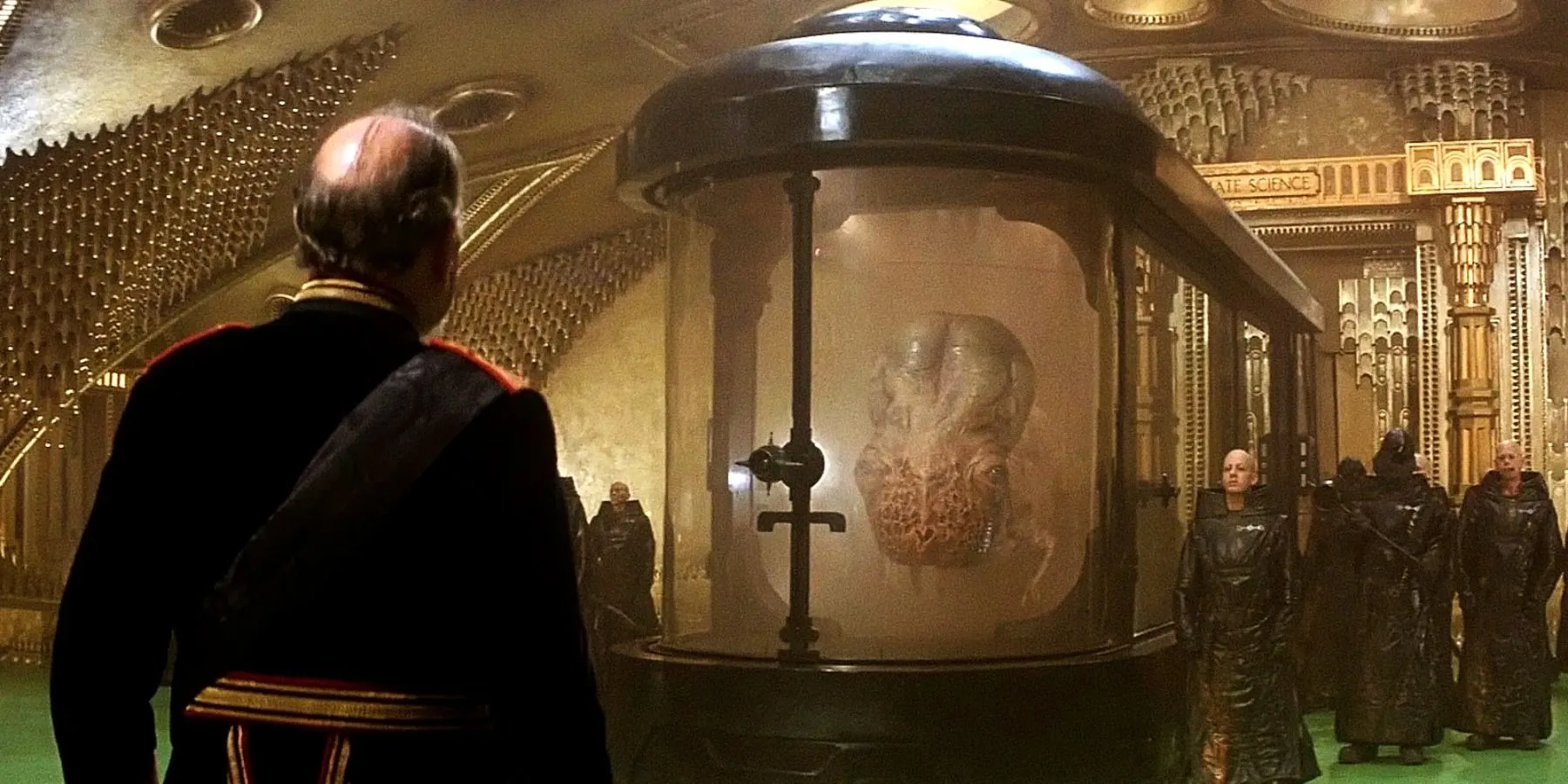

In addition to character portrayals and aesthetics, the narrative differences present intriguing points to ponder, especially as Villeneuve chose a slower, more deliberate storytelling approach across two films. However, this meant that significant elements such as the Emperor’s dependence on the Spacing Guild were omitted in the newer take. Lynch’s adaptation included this crucial aspect in its trademark style, portraying the Guild Navigator as a large, mutated reptilian figure. Villeneuve, conversely, opted to hint at the Guild’s influence through human representatives. In an interview with Empire, he explained his intention behind the omission:

“We don’t see the Navigators in this first part […] I tried to keep all the space-traveling as mysterious as possible, almost evoking a sense of mysticism regarding that part of the narrative. Everything relating to space feels enigmatic.”

Reassessing Lynch’s Dune

The earlier portrayal of the Spacing Guild in Lynch’s Dune not only amplified the film’s eccentricities but also imbued the narrative with deeper political implications by showcasing how a seemingly unmatched ruler like Shaddam IV must adhere to the Guild’s authority. The depiction of interstellar travel became all the more intriguing, particularly with the sequence illustrating the Navigators creating a wormhole, evoking a ritualistic quality. Nevertheless, some of Lynch’s more controversial decisions, such as transforming the Bene Gesserit’s voice techniques into physical Weirding Modules, complicate the credibility of his more inventive choices.

Lynch’s Dune also deserves acclaim for its sound design and musical score, which, while differing notably from contemporary interpretations, successfully maintains its own identity over the years. Certain stylistic choices, such as utilizing voice-overs for character reflections, may come off as cluttered to some viewers, but this creative risk should be appreciated. Overall, the 1984 adaptation warrants a renewed viewing, especially as audiences are beginning to embrace the “campiness” associated with older films that were once undervalued. After all, any Dune adaptation featuring Sting as Feyd-Rautha and including space-handling pug dogs cannot simply be overlooked.

Leave a Reply